By Gaylene Preston

Landfall 205, Autumn 2003

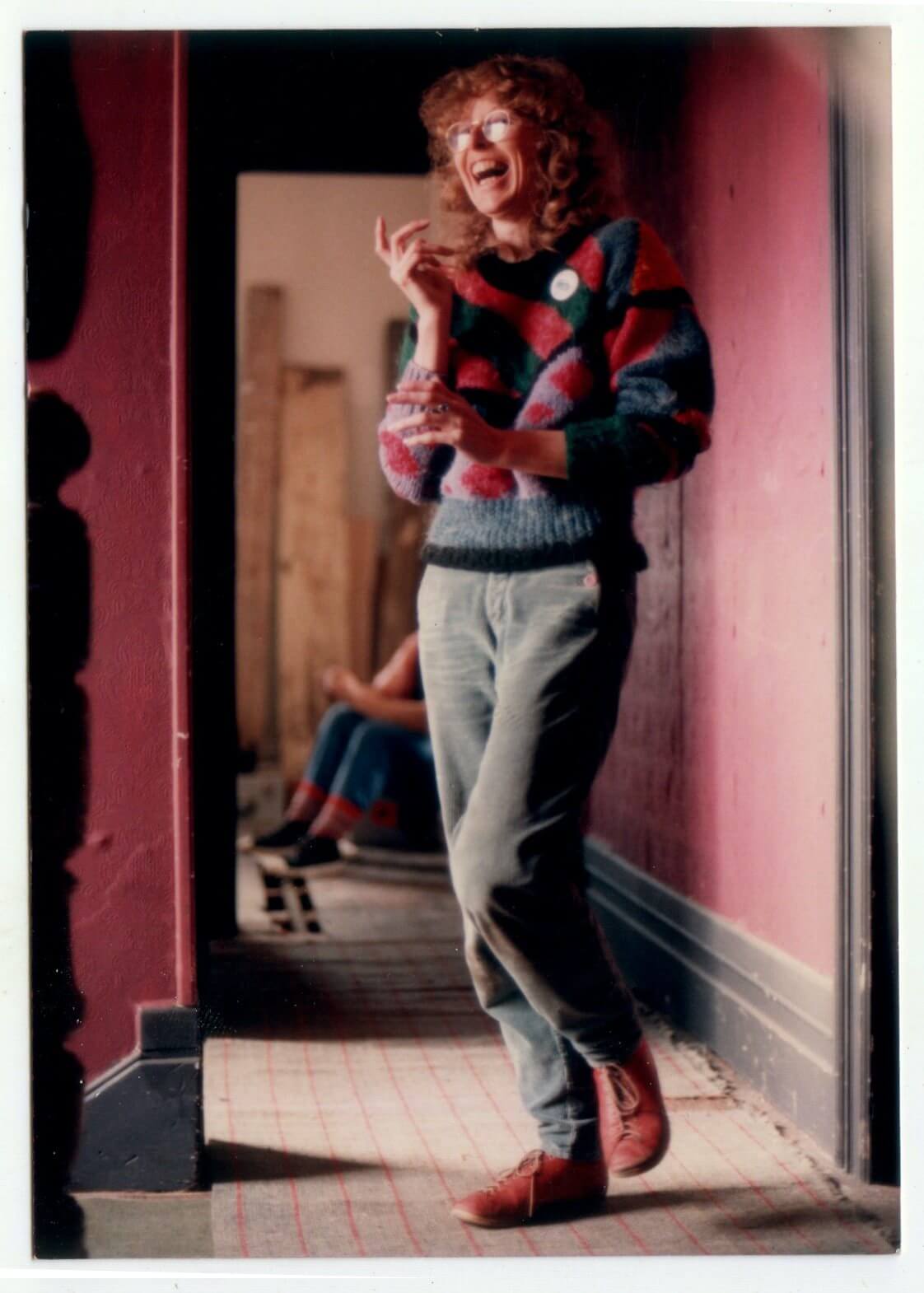

I’m wearing my polka-dotted Ossie Clarke trousers and my boots I painted rainbows on. I’ve been deposited in the darker reaches of Kilbirnie, the southerly raging as Martin drove me though the gloom of the Mt Victoria tunnel in his Austin Seven with the window screen wipers barely coping. ‘They built this during the depression.’

Accounts for the gloomy pinched narrowness with only light at the end so bright. Blinding Kilbirnie. My sister has bossed us out here. She’s a force to be reckoned with, my sister. I’ve turned up from England, all scrawny and white apparently, with a suitcase the New Zealand Railways fucked forever and $500 in my post office savings account. ‘But what are you going to do?’ They all asked. Not a question. Scary. I was doing it wasn’t I? I came home didn’t I? Seven years later, I am here. YOU ARE HERE. X marks the spot.

So I’m standing in John O’Shea’s office in ‘the White House’. It’s only white on the outside. Orange and brown with white and grey wallpaper – run down suburban 60s on the inside. ‘I don’t care what I do,’ I’m fond of saying. ‘There’s lots of things I can do…’ Tails off about there. John’s a large literate man in shirtsleeves chain-smoking rollies. The ash falls on to his tie and he absentmindedly flicks it aside as he continues viewing my ‘portfolio’.

Radical Feminist cartoons mostly. ‘I did these in a cartoon collective for a London-based magazine for radical social workers,’ I tell him, trying to ignore the quizzical look in his eye. ‘They’re cutting everything except the grass,’ two cartoon women sitting outside a council estate high-rise commiserate. I wonder how this translates to Muldoon’s Godzone, where unemployment is 3 per cent (dole blugers) and the cradle-to-grave social security state has been shaken by the oil crisis but not yet stirred.

‘A bad moment,’ he tells me. Pacific scrambles for business in uncertain times. ‘Y-you should see them at Avalon.’ Avalon. The city of the dead in Arthurian legend, but in good ol’ Godzone it’s Television Land. The government has built a big multi storied concrete tower in the middle of the paddocks overlooking Hutt River. A brand new television complex for a brand new Television Nation. Everyone watches. Streets deserted after half-past-six. They’re sitting in their la-Z-Boys eating chops and mash and Watties as Dougal reads the news and the brave boys take on Muldoon and everyone yells a bit on Close To Home and the whole country is watching when Mavis’s budgie in Coronation Street lays an egg but it was supposed to be a boy budgie! Pacific have been making documentaries. Director-led docos. Barry Barclay’s ‘Tangata Whenua’ series. Tony Williams and Micheal Heath’s The Day We Landed on the Most Perfect Planet in the Universe. But I still haven’t seen these films at this point. ‘I just want to be part of a creative group,’ I tell my sister. ‘You need to go out to Pacific films then,’ She has just composed and recorded the music for Hunting Horns: James McNeish on China. Directed by Barry Barclay. Music by Jan Preston. They even paid her too. And a documentary hour is fifty-five minutes of care and attention and time to think on the telly. Two commercial breaks. Marvelous.

And I’m standing there looking at the rainbows on my boots as the dots on my trousers polka and this chain-smoking pillar of New Zealand film making is kindly and completely dismissing me from his creative cauldron. Just about the only one in the country. I look up and shrug. ‘I’ve worked seven years since art school in various institutions, some of them of a fairly total kind, and I don’t want to work in them anymore. So I won’t be going out to Avalon.’

As I left, he introduced me to this bearded bear of a blue-jeaned bloke in cowboy boots. ‘Rory, this is a film-making Sheila. An old dropout trying to drop back in again.’ They laughed the O’Shea laugh. Like water over gravel – phlegm ravaged lung with a rattle of mischief. I didn’t know till a while later: I’d got the job.

It was the one they didn’t have. ‘You can come and art-direct.’

‘But I have no idea what an art director does.’

‘Don’t worry about it, it’s a s-secret profession. Nobody knows.’ That laugh again.

‘Well you’d better put me on a couple of months’ trial because I only know about loony bins.’

‘P-perfect training.’

So I’m now a proper professional. Fully paid ($90 a week for as many hours as it takes), Pacific Films’ ‘new art director from London’. And I haven’t the foggiest clue what I’m up to. And, more frighteningly, neither has anyone else. I take to slyly sidling up to unsuspecting (I hope) graphic artists with fully paid nine-to-five jobs at the National Film Unit in Miramar ($170 a week with superannuation and a subsidized café for a eight-hour-day, five-day week). Actual art-school graduates, they know what they’re doing. ‘I’m not sure where to get materials,’ I lie. They concur. Living with imposed import restrictions, it’s like living in Romania, not what you’d be used to in London – ‘and why did you come back anyway?’ I’m starting to wonder myself. They would then show me ways to do things in ‘this bloody country’. I’d nod sadly amid a certain amount of tut-tutting, leap into the Pacific car and whiz back to Kilbirnie to try it all out before I forgot anything.

In such a way, I managed to do graphics for the Pacific films nearing completion (Autumn Fires: Martyn Sanderson talking to his aunt Olive Bracey in the Hokianga; Korowai: weaving with Rangimarie Hetet, directed by John Reid) and every day at morning and afternoon tea I’d sit in the tearoom where strong tea brewed in a big aluminum pot and people would emerge from the bowels of the big building to drink, have a breather and swap film talk. Film talk. It’s completely incomprehensible to the unitiated. ‘Mag track’s drifting, must be a problem with the crystal.’ ‘Picture’s held well on the 600, but a bit soft in the middle there.’ I learned it by osmosis in the tearoom. Nowadays it would be called a knowledge-wave incubator. Back then it resembled a shearers’ tea-break more than anything else. We sat on orange vinyl squabs under a pall of smoke.

Amid all this deeply mysterious chatter, I finally solved the mystery of how I got hired. John O’Shea, with the wit and pure white-raged vengeance of a true-blooded Irishman, hated them out at Avalon. Acerbic and ‘ungrateful’, he had spent a lifetime trying to tickle money out of the Broadcasting Combine, a job that had become harder and harder as the only television network in the country became more-or-less exclusively an entirely in-house institution, locking out the few existing independents. Outside ‘experts’, mainly from Britain, had taken over. Pacific had gone from being a small powerhouse providing a full slate of well-made auteur documentaries to being a maker of training films and commercials, struggling on with antiquated gear and no TV commission. John seemed to blame the current director-general personally. ‘The only time a rat joined a sinking ship,’ he had been heard to mutter. An angry Irishman who became funnier and more eloquent the angrier he got, he tested would-be hopefuls washed up at his door by suggesting the Avalon option. It was his way of getting rid of them. My strongly negative reaction had been noted with surprise. He must have remembered me when a Sydney-based ad agency suggested that Pacific would get more work if they had an art director.

To say John had a conflicted attitude towards making commercials would be an understatement. They were the only work that Pacific did that paid a healthy profit, but he despised having to do them. That was obvious to me on day one.

That morning I had got on the cable car and caught the bus to Kilbirnie. I’m delivered outside Pacific Films, bright-eyed and bushy-tailed at 8.45 am. The place is deserted. A chill wind blows down Cruickshank Street. I’m in a ghost suburb with not an instant coffee in sight. I wish I’d never left my nice friendly gas-central-heated urban commune in Stockwell Park Crescent where we endlessly discussed the politics of housework and knew all about dialectical materialism – sort of. Karl Marx would have been completely stonkered if he’d had to account for Muldoon’s Kingdom. ‘Fish out of water’ doesn’t start to describe how I’m feeling. This is supposed to be my pond. Everything in it is so familiar - lamp-posts, washing lines, bungalows, Morris Minors. But I’m an alien being here, a square peg. I don’t belong.

Eventually a slightly worse-for-wear white Mazda turns up and out gets a small, natty-looking man with a moustache and wearing a very-neat sports coat and tie. Eric Anderson, the accountant. It wasn’t a very auspicious meeting. I have a moustache prejudice and he wasn’t too pleased to seem me either. I suppose I was just another hungry mouth to feed. But he is pleasant and amid much rubbing of hands in the cold I’m taken into a sprawling dark concrete building, shown the kettle and told not to turn the second bar of the heater on. People wander in, quite a scruffy lot I note with relief. No more moustaches. Beards I can handle. The last to arrive were the directors. Noisy John Reid - a friend from university days in Christchurch – and Barry Barclay. He had seen my 8mm film – Creeps on the Crescent – ten minutes of silliness made with my London mates. I had brought it in to show John. Barry congratulates me. Here’s this man, one of the few experienced film-makers in the entire country, making me feel like I’m the clever one. My heart doesn’t leap but that chill wind lets up a little.

John O’Shea is the last to arrive. He and Rory are trying to sort out who could do an extra unexpected task – clearly not me because I know nothing. More jokes at my expense. John looks at his watch and leaps up, bidding me to follow him to the screening room. They are presenting a commercial to the agency people. It’s a training film for New Zealand Breweries bar staff – twenty minutes on how to pour beer really fast from hoses – with the Pacific Films in-house working title Piss Pour. As we head over there, John tells me about the agency fold. ‘For really clever people, they’re quite stupid actualy.’ Cheerful disdain. We head through the little dark labyrinth of the old bakery to the double-head screening room.

As we are about to enter, John blocks me from the view of the assembled men in suits, grabs a friendly looking character standing by the doorway, pushes our heads together and whispers, ‘P-pretend you know each other, alright?’ With that he continues into the room, leaving me shuffling about looking into the equally bemused face of a complete stranger. ‘ Yea, well then… how’z a goin.’ ‘This is Gaylene, our new art director from London’, John tells no one in particular and the lights go down.

Crunch, that was his name. Why ‘Crunch’? ‘Crunch the lunch.’ They had a nickname for everyone. They called me Bruce.

I was the worst art director you could think of. The first job I had to do was to fix the sign on ‘Chloe’s Wine Bar’. They’d put the apostrophe in the wrong place in Piss Pour and it had to be re-shot. Well, I could do that OK. Had to get a man to help me with the ladder, though, and the hammer, and the nails.

The second job was to art-direct a commercial for a sheep drench. That involved talking Dr Margaret Sparrow into allowing us to use her surgery as a location and bring a sheep in to be ‘patient’ to Ross Jolly’s ‘doctor’. John Reid was directing and was very keen to have a skeleton hanging in the back of shot. Apparently it was the art director’s job to go out and find one – which I did – from the very reluctant and quite scary tutor sister at Wellington Hospital. ‘His name’s George. He’s very fragile, you will be careful with him, won’t you.’ ‘Absolutely,’ I assured her as I bundled George into the back of the Pacific Films Holden Kingswood, doing my best to hurry before she changed her mind. George never really recovered from this experience.

I got him up the stairs to Dr Sparrow’s Kelburn surgery alright, but he came apart a bit on the way down. It was the usual thing for those days. The shooting crew (at least five people – to me an unbelievably huge behind-camera crew) worked for thirty-six hours over a weekend, then the ‘Art Department’ (me) and ‘Production’ (Crunch) cleaned up. By that time it wasn’t just George who was coming apart. So we wired him up on Monday morning and took him back, but as Crunch was thanking the teaching sister, I was in a cold sweat, hunched over George in the cramped quarters of the back of the station wagon, trying to hook up his last remains. He came out of the car looking alright but every so often I find myself wondering if the fact that I am pretty sure I put one of his arms on back-to-front is going to lead eventually to real problems in the fracture clinic.

So I settled into work at Pacific. Work until it’s done – sometimes all day, all night and all the next day, until my eyes felt like the bottom of Mavis’s budgie cage and everything seemed to be seen through the wrong end of the telescope. I harped on and on to John until he let me direct something. A twelve-minute piece titled ‘Toheroamania’ for a series called Shoreline – a water-bound Country Calendar which never really took off but should have. By the time I was sacked six months later I was a director. ‘Madame le derecteur’, John proclaimed after the double-head of my first effort. But he had to sack fourteen people one day. The combine had finally got him. It wasn’t the end, though. He kept going. Plenty of films still ahead for him – and, fortunately, for me; because I can’t work in institutions and now, to add to that, I’m pretty much unemployable in any other medium.

On my last day at Pacific I was working in a large room euphemistically called ‘the art room’ Harry Wong was reputed to have been the one who painted it black. I was spotting some black-and-white photographs, a tedious process involving a very fine paintbrush and black water-based paint. John came in and sat down at one end of the large littered worktable. The day had been long and difficult for him. I was the last to come, so I had been the first to be told to go. I was the easy one. The rest were longstanding – family, really. The golden years of Pacific TV documentaries were gone forever. As he spoke, the sun set over the bus depot across the road and the trolly bus sparks grew brighter until they were like explosive punctuation marks against the darkening sky. After a while the street lights came on, casting orange stripes over the gloom. I had stopped working, not wanting to interrupt by turning on a work light. By then John had become a film noir shadow articulated by the glow of his ever-present cigarette. As his monologue became more and more retrospective, he told me everything he thought I needed to know to be an independent film-maker in this funny little big country so surrounded by the deep Pacific. The other rolling raging Pacific. If ever a sea was so misnamed, it has to be the Pacific.

What I remember most vividly is a story he told me about when he was shooting Runaway. ‘R-runaway’, he always called it. He made it in the ‘60s, a lone feature-maker forging a path no one was at that time all that interested in. ‘We went to an alpine southern lake. The light wasn’t right. We waited for three days. The sequence l l-looked terrific.’ A long pause. ‘I’m still p-paying for that.’

A week later, I stood at the top of Kelburn Parade looking down on the glittering jewel that is Wellington on a crisp winter morning just after a southerly. And I had a bit of a moment. My stomach turned over and my palms were clammy. I realized that I wasn’t going to be able to leave this place until I had made a feature film of my own. I tried to make the idea go away but I knew it had come to stay. And in that moment, socialist feminist cartoonist stirrer and wanderer- returned, I finally landed.